- HOME ›

- Speech delivery ›

- How to practice a speech

How to rehearse a speech

- to rehearse or to 'wing it', that is the question

By: Susan Dugdale

Do you know how to rehearse, or practice, a speech?

Do you know how to structure the time you have between preparing, (writing), your speech and delivering it well?

What do you think you should focus on first?

If you want to rehearse, rather than 'wing it', but really don't know much about the process, you're in the right place.

Jump straight to the 3 important pre-rehearsal options you need to review and then on to the 7 'how to rehearse' tips.

To 'wing', or not to 'wing it'?

There's a fairly large group of people who have convinced themselves there's no real need to rehearse a speech at all. They prefer to 'wing it'!

Perhaps that's been your preference too.

Here's the strangely crooked, yet compelling thinking that often sits in behind the decision to 'wing it'. It delivers a win if you fail AND a win if you succeed.

When 'winging it' works

For example if I go out there and, with minimal preparation, wow the audience that's proof preparation, rehearsing, is a waste of time.

Who needs it? I don't. They laughed at my jokes. They asked me questions, and they told me I'd done really well. I'm good, without practice.

When 'winging it' fails to fly

On the other hand, if I go out there and forget to mention several critical points I was supposed to make, nobody laughs at my jokes, and the audience is restless the entire time I'm speaking, that's understandable. Because, after all I was 'winging it'.

I wasn't really trying. If I had, I would be so much better!

That aside, this lackluster result doesn't count. I don't need to feel embarrassed because I hadn't committed myself to do the very best I could in the first place.

'winging it', accountability and self protection

In many instances 'winging it' is a way of avoiding accountability. It's a form of self-protection, a shield to hide behind. After all what might happen if you genuinely put a whole lot of work in and despite doing that, fail?

That would feel hard, and very painful. It could be enough for some to say, why bother? And walk away shrugging their shoulders.

(However, that is not you!)

Got the words sorted, so the speech is done.

Alongside 'winging it', there's another common assumption. This one is about the speech itself; the content, the words you say.

The assumption is that once the content is decided on and prepared, the speech is ready for delivery.

You do not need to do anything more. Because, heaven forbid, you would sound robotic, or false, if you practiced.

I want my speech to be real, to be natural

When the time to deliver the speech arrives, you open your mouth and the words come out.

It's spontaneous. It's natural. And whatever happens, is fine because it's real.

'Umming' & 'ahhing', gear mishaps, and awkward silences

That includes all the unconscious speech habits you may have: 'umming' and 'ahhing', awkward pausing, gabbling caused by nervousness, fidgeting, and so on.

In addition, it also covers any other unforeseen events.

For example, glitches with gear because what was required wasn't thought through, like these:

- The lead brought along for the projector not being long enough to reach the wall socket.

- The cue cards not being numbered. When dropped it takes an age to figure out the order they should be in.

None of these awkward moments need happen. They may be natural but that doesn't make them good.

Please understand that ...

Rehearsing can make ordinary extraordinary

Think about it.

Writing is only part of the process. It's delivery that completes it.

Despite what you may have been told, and want to believe, the act of giving a speech is performance and delivering it well takes practice.

Ultimately 'winging' it will let you down

If you've sat through ho-hum presentations finding your finger nails more interesting, the odds are the delivery was less than polished.

The content may have been excellent. It may have been well researched but because the speaker lacked basic delivery skills, the entire speech was compromised.

That is why, if you care about your audience, your content, and yourself, you need to know how to rehearse.

Rehearsal refines your speech

It helps you to identify areas needing work. For instance:

- Is the opening effective?

- Do the transitions from one idea to the next work?

- Do you need to slow your speech rate? When? Are some parts better faster or slower?

- Do you need pauses? Where? How long for?

- Are your words clearly spoken? Can people hear you adequately?

- Are any props you've planned fully integrated into the flow of your speech?

- Is the ending strong?

- Does the speech fit the time allowance?

All this, and more, you'll find out through rehearsal or practice.

How you deliver a speech makes a HUGE difference. Good delivery helps you to reach out and communicate well with your audience.

Pre-rehearsal

Before you begin learning how to rehearse you need to make a critical decision. What you decide will have an impact on how you practice and deliver your speech.

Make a choice between:

- Reading your speech from a word-for-word

script.

This is where you have EVERYTHING you are going to say fully written out. - Using cue or note cards on which you

have written the headings of your main ideas in order and the key words associated with each of them.

(Cue cards are easily made from small index cards. One is used per main idea and its key words and phrases are clearly written on each. You speak from memory using the keywords/phrases as a trigger.) - Committing your entire speech to memory. In this option you have neither cue cards or a script.

There are positives and negatives for all three options.

Word-for-word script

Using a full manuscript (a word-for-word document) can be positive as it acts as a safety net for a nervous or first time speaker. The downside is reading.

When people read they tend not to make eye contact with their audience. And neither is their voice projected outward. Instead it's focused downward to the page.

If the script is in their hands, rather than on a stand, then they're not free to gesture and there is always the temptation to mask or cover their face with it.

If a stand is used to place papers on, then it's between them and the audience, creating a barrier.

There are ways around these problems.

- The first is to place the stand to one side instead of directly in front of you.

- The second is make sure the stand is at eye-level to ensure easy upright reading.

(You won't be bending down and therefore presenting the top of your head rather than your face to the audience.) -

Another is to make sure the script is easily read.

A mess of scribbled notes isn't good! If you lose your place, you'll be struggling to find it. Type them up in a clear good sized easy-to-read font, double space and number your pages before printing them out single-sided. - And to practice reading your speech aloud.

The ability to read well aloud is a great skill to have, and particularly useful if you have to give a speech at very short notice.

Visit How to read a speech effectively for specific tips to ensure you don't put your audience to sleep. :-)

If full scripting is your choice, make a clean copy of your speech before going on to the 'How to Rehearse' tips.

Cue or note cards*

The positives for using cue cards are they are smaller than a full size script and therefore can be held unobtrusively in one hand. Because you are not using a stand for notes you're not blocked off from your audience. This means you can use eye contact more easily and direct your speech where you wish. And because you're not following a word-for-word script, you're freer to be more spontaneous.

The downside of cue cards is apparent if they haven't been prepared properly.

If they're not ordered you run the risk of getting muddled. If they're not clear and easily read, you run the same risk. The other major negative is what happens if you stumble in remembering how you linked your ideas together.

If cue cards are your choice, you'll need to prepare them before you go on to the How to Rehearse tips.

You'll find a page of instructions here on how to make good cue cards.

*The term 'cue' comes from theater. A cue for an actor is a signal to begin speaking, or enter, or do some other action required by the play.

Memorizing your speech

The positives for committing your speech entirely to memory is that you meet the audience completely free of notes. You can gesture, ad lib etc where you wish, provided of course, that you can keep yourself on track.

While this option is good for speakers used to being in front of people, it can be daunting for a novice. It is also difficult to pull off with certain styles of speech.

For example, if you are giving a complex business presentation which includes the breakdown and analysis of large chunks of data, this would be risky. So think carefully and wisely before making the decision to go solo.

Styles of speech most suitable for giving entirely from memory are eulogies, wedding, retirement speeches...the type which include personal story telling. Here it can work brilliantly, although you do need to keep in mind that rote learning, without expressiveness, can make delivery wooden.

Click the link for more information on using acronyms as mnemonics (memory aids) to help remember your speech.

If memorizing your speech is your choice, pay particular attention to expressiveness when it comes to the 'How to Rehearse' tips.

How to rehearse tips

Aim to have a minimum of three rehearsals before your final presentation in front of an audience. If you have the time available for more, take it.

The more you run your speech through, the more confidence you'll have and the easier it becomes to deliver it more effectively.

The first two rehearsals are to iron out any glitches in either your text or delivery and to integrate any resource material you may be using. These could be photographs, a power point presentation etc.

The third is a dress rehearsal for the real thing.

How to rehearse tip one: reading aloud

Read your speech notes several times out loud. Do the same thing if you are using cue cards.

Hearing yourself speak will help you to familiarize yourself with the flow of your material more quickly. It will also help you to spot potential difficulties more easily.

If you find some phrases awkward to say change them. Similarly if you notice leaps in logic fix them.

Time the speech. If it is too long for the time allocated, cut it to fit, aiming to end before you are required to.

During this beginning phase do not worry about expression or gesture. You will cover that in 'tip 3'.

Right now your primary focus is on getting the flow of the content fluent. That means without jumbling the order or hesitating because you've forgotten what you planned to say!

How to practice tip two: watching yourself

Now record yourself using the camera on your smart phone. Then play it back.

Actually seeing and hearing yourself while presenting is a revelation. You can no longer hide in the comfortable illusion of what you 'think' you do. This is your own reality TV show.

You will see the good, the bad and the ugly. The good news about that is that you are giving yourself the opportunity to learn - to become better.

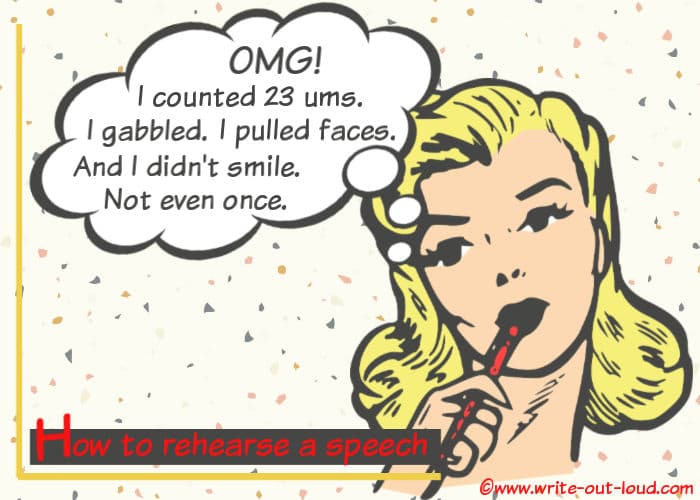

How to rehearse tip three: delivery demons

While watching yourself look out for anything hindering your communication, either in your body language or speech.

These delivery demons could be:

- Habitual unconscious gestures like fiddling with your hair, pulling faces when you can't remember what is next, standing awkwardly, swaying, pulling at your clothes...

- Irregular breathing running you out of breath over long sentences or holding your breath which makes your voice sound strained.

- Racing your speech through

- Pauses or breaks in the wrong places which weaken or alter your meaning

- Specific words or phrases that trip you up e.g. a name

- Holding your notes in a way that masks your face

- Rattling or fiddling with your notes if you are reading from them

- Hiding behind, or slouching over, the stand if you are using one

- Dropping or raising your voice at the end of sentences

- Mumbling

- Repeated phrases eg. 'and then I...','and then I...', 'and then I...'

- Repeated fillers eg. 'um', 'err'...

- Lack of gesture or too much of the same gesture

- Lack of eye contact or smiling

- Minimal variation in tone or pace

- Bumbling the use of resources through not having them organised.

How to rehearse tip four: fixing the faults

When you see/catch yourself committing any of the grievous speech delivery crimes listed above under 'delivery demons', STOP.

Take a very deep breath, fix the problem and start again from where you left off.

Help is a click away

You can find help with speech rate (either going too fast or too slow) by clicking the link.

If you find yourself mumbling and running words together try using some of these diction exercises.

If you need to work on pausing and breathing effectively you'll find these exercises help.

Click this link for assistance with vocal variety issues, like monotone delivery and lack of expressiveness

Go to this link for gesture and body language tips.

Do be patient with yourself.

Some of the habits you've just become aware of will be deeply ingrained. It will take sustained effort to create new, more beneficial ones. However the more practice you do, the quicker you'll get there.

How to rehearse tip five: making notes

If it's a matter of when and where to pause either for a breath or to stress an important point, mark it on your cue cards or script.

In the same way mark passages needing to taken more slowly, or words requiring extra emphasis.

Make whatever notes you need to remind yourself of what you want to do to improve your delivery.

How to rehearse tip six: using humor

Humor can be incredibly difficult to get right. One person's funny, is another person's not.

If you have included jokes, they need special timing attention. Point up the cue for the audience to laugh by briefly holding back the punch line and leave space for the audience to respond before carrying on.

For your own self-preservation click for more information on How to Use Humor Effectively. You need to know your audience!

How to rehearse tip seven: the dress rehearsal

Testing, testing, testing ...

- Run through your entire presentation as though it was the real thing. And if possible, do it in the venue you'll be using.

- Wear the clothes you'll be wearing for the event so you can be sure you feel comfortable and that they're not restricting in any way.

There's a helpful personal grooming checklist here with guidelines on choosing clothing. - Set up your stand, if you are using one, in a similar position to the one you'll use on the day.

- If you are using any electronic equipment for example a microphone be sure to rehearse with it.

Can't make up your mind whether to use the podium microphone or attach one to your lapel? The pros and cons of both are discussed here. - If you can present to trusted friends or a members of your family, do it! Their feedback could provide in valuable last minute suggestions. Tell them exactly what you want feedback on before you start. Ask them to take notes during your speech to give to you after it's finished.

- Do not STOP if you falter. Keep going.

- When you're done make any minor adjustments you need to and repeat to integrate them.

Rehearsing a question & answer session

And lastly, if your speech/presentation includes a question and answer session think through the types of questions you are likely to be asked. Prepare answers to cover them and practice delivering those as well.

It's tempting to think that once you're through the prepared speech the rest will fall into place easily. However if you haven't put the thought and preparation in it will be transparently obvious! And you could undo everything you've worked so hard to put in place. That's a risk so easily avoided. Don't take it.

And very lastly ...

Here's a couple more pages you might find useful.

The first is the perfect complement to this one: how to practice public speaking. In this article I cover aspects like segmenting your practice, how to get useful feedback, how to deal with distractions, and more. The topics supplement what you've already read about on this page.

Go to how to practice public speaking

The second page covers 5 strategies to tame public speaking fear.

The last of the 5 suggestions is to create and work what I call a Bring-it-On list - a comprehensive preparation checklist to minimize the possibility of anything under your direct control going sideways and jeopardizing your presentation. You'll see my example list contains many of the items mentioned here plus some more.

To get you started I've made a printable checklist. Download it. Take my list and adapt it to fit your own situation.

Collect the printable from 5 strategies to beat public speaking nerves.

- Return to top of how to rehearse